As we navigate the swift currents of the 21st century, we often find ourselves immersed in a sea of dismissive attitudes towards the past. Today, casual conversations are awash with cavalier references to the supposed outdatedness of bygone eras and the irrelevance of our ancestors’ traditions. In these discussions, snide remarks about the current age often serve as the final word, leaving little room for counter-argument.

Religion and politics, once hotbeds of passionate dialogue, are now often deemed too controversial or polarizing to broach. The irony is palpable — in an age where we are ostensibly more connected than ever before, we seem to have lost our ability for engaging in meaningful, substantive discussions.

Unlike many of my contemporaries, I have always been a proponent of spirited debate. As I’ve grown, married, and started a family, my views have evolved, prompting a renewed scrutiny of these conversations. I reflect upon interactions with those firmly entrenched in our nation’s rapidly changing cultural landscape — individuals who subscribe wholly to the notion that the world’s architects were nothing more than superstitious, bible-thumping fools. This perspective deserves challenge and re-evaluation.

Many of my former acquaintances were fervent advocates for secular liberalism. In the heat of our debates, a recurring theme surfaced—that life, according to them, bears no inherent meaning and our ancestors clung to their beliefs solely due to their naivety. They posited that religion served merely as a social control mechanism, no longer holding any relevance in our contemporary era. Essentially believing that we are all just bags of chemicals walking around, doomed to nothingness after death. A perspective I find as depressing as it is pointless. These same people, are willing to go so far as to label our ancestors as ‘primitive humans’ grappling with their world—a world we now assert, with a hint of arrogance, to ‘fully comprehend’ through the lens of science.

I find myself bound to challenge this presumption. To declare we ‘fully understand the world’ or to categorize our forebears as ‘primitive’ is a stance I deem fundamentally flawed. It’s a viewpoint that can be readily debunked if we pause to appreciate the intellectual prowess of these so-called ‘primitive humans’. Let’s momentarily examine just a fraction of the milestones that have brought us to our current level of understanding, and the intellectual giants that brought us here.

The Egyptian Pharaoh Tutankhamun exhibition, currently touring the country for the first time since the 1970s, provides an unforgettable immersion into the world of this ancient civilization. Even a cursory glance at the fascinating showcase was enough to reveal the undeniable intellect and brilliance of our ancient predecessors.

Far from being a society of savages, the civilization that masterminded marvels such as the Pyramids, the Sphinx, and the sprawling necropolis of the Valley of the Kings demonstrates a sophisticated level of understanding and capability. The exquisite golden sarcophagus of Tutankhamun, the intricate wall paintings in his tomb, and the wealth of artifacts unearthed there are testaments to a society that excelled in diverse fields such as art, engineering, and administration. These tangible works of genius boldly contradict any notion of primitiveness and affirm the intellectual prowess of our ancestors.

The Rosetta Stone is another shining testament to the grandeur of the ancient world. This remarkable artifact, crucial to unlocking the secrets of Egyptian hieroglyphs, bore the same text in three distinct scripts: Greek, Demotic, and Hieroglyphic. For centuries, these cryptic symbols remained a riddle, their meaning shrouded in mystery. However, thanks to the Stone’s Greek text, scholars were able to decipher the undecipherable, paving the way for a deeper appreciation and understanding of ancient Egyptian civilization and its vast cultural contributions.

Adjusting our focus from Egypt to Greece, we encounter another civilization far from primitive. The ancient Greeks made indelible contributions across a diverse range of fields, their profound insights echoing through time. The unerring precision of Euclidean geometry, the revelatory implications of the Pythagorean theorem, the pragmatic wisdom found in Archimedes’ principles, the intellectual rigor embodied in Aristotelian logic—each speaks to a deep and sophisticated comprehension of the world.

Yet, I propose that even their remarkable practical insights are surpassed by their philosophical acumen. Consider Socrates’ insightful words from ‘The Republic’:

“The excessive increase of anything often causes a reaction in the opposite direction; this is true of the seasons, individuals, and governments… The excess of liberty, whether in states or individuals, seems only to pass into excess of slavery.” (The Republic, Book VIII)

Penned almost 2500 years ago, this wisdom resonates with uncanny relevance, encapsulating core issues we grapple with in today’s society. Yet some suggest we should discard the wisdom of such ancient minds because they lacked our understanding of cellular biology—an argument that seems hilariously narrow in perspective.

Beyond their intellectual achievements, the ancient Greeks were pioneers in societal constructs. They fashioned a democratic system and the concept of citizenry—innovations that continue to shape societies around the globe. Their enduring influence belies any simplistic notion of them as primitive.

Transitioning from the Hellenic era to the epoch known as the Middle Ages, or disparagingly as the ‘Dark Ages,’ one might be tempted to succumb to the idea that this was a period devoid of intellectual progress or innovation. However, this widely held perception warrants a challenge. Central to the intellectual preservation during this era was the indomitable presence of the Catholic Church. The Church not only preserved the remnants of the old world’s wisdom but served as a beacon of learning, carrying the torch of knowledge through the darkness of these ages.

During this tumultuous period, monastic schools and universities were established under the aegis of the Church. Far from being solely religious institutions, these centers of learning were repositories of various fields of study, preserving the intellectual legacy of the ancients and shedding light amidst the encroaching shadows.

A prime example of the intellectual richness fostered by the Church is embodied in the work of St. Thomas Aquinas. His monumental work, Summa Theologica, offers a profound testament to the theological and philosophical discourse of the time. A pivotal excerpt reads:

“Nothing can be moved (changed) from a state of potentiality to actuality except by something already in a state of actuality. […] This series cannot go on to infinity because then there would be no first mover and, consequently, no subsequent movers. Therefore, it is necessary to arrive at a first mover, moved by no other; and this everyone understands to be God.” (Summa Theologica, I, Q. 2, Art. 3)

Aquinas’s intricate arguments and systematic approach, as demonstrated in this passage, bear testament to the intellectual potency of the era. They effectively counter the narrative that religious belief impeded progress. Rather, faith was a guiding light in those times, a beacon that helped humanity navigate the turbid waters of the ‘Dark Ages’, ultimately steering us towards the enlightening shores of the Renaissance and laying the groundwork for our contemporary understanding.

Moving forward into the epoch of the Renaissance, we encounter a dazzling array of intellectual and artistic brilliance. This era, characterized by a veritable explosion of creativity and knowledge, is a testament to a significant leap in humanity’s intellectual and artistic evolution. The Renaissance period’s grandeur sharply refutes the notion of a civilization mired in primitivism, instead shining as a beacon of human potential.

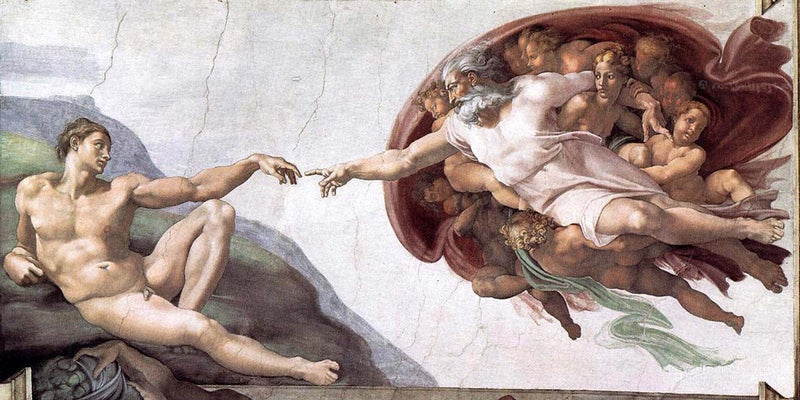

Center stage in this grand tableau stand luminaries such as Leonardo Da Vinci and Michelangelo. Their genius, far-reaching and multi-dimensional, transcended the confines of mere artistry to embrace a myriad of disciplines such as anatomy, physics, and engineering. Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man is not merely an artistic masterpiece; it also embodies a profound understanding of proportion and the human form. Similarly, Michelangelo’s David or the awe-inspiring frescoes of the Sistine Chapel are not only remarkable for their aesthetic beauty but also for their intricate understanding of human anatomy and the artist’s ability to translate that understanding onto marble and plaster.

The masterpieces of Da Vinci, Michelangelo, and their contemporaries didn’t just spring from a vacuum. These works of genius were borne out of a civilization deeply rooted in a rich legacy of knowledge and learning, a legacy nurtured and carried forward through generations. Far from being the sudden, unheralded blossoms of a ‘savage’ society, these works reflect the pinnacle of human intellectual and artistic achievement—an achievement whose reverberations still touch us today.

These exceptional individuals and their timeless creations counter the assumption that our ancestors were ‘primitive’. Instead, they attest to a powerful truth: we, the denizens of the modern world, are not so much forging new paths as we are traversing trails blazed by intellectual and artistic giants whose shoulders we stand upon.

As we delve deeper into the grand symphony of human achievement, we find ourselves amidst the golden era of classical music. This period, brimming with intellectual rigor and emotional depth, further dissolves the baseless notion of our ancestors as primitive. It was an era that witnessed the harmonious blending of science and art, a testament to the refined sophistication of the time.

Consider the incomparable Johann Sebastian Bach, a figure who has transcended centuries, his music still filling the halls of concert venues around the globe. Bach, an unquestionable genius, was known to inscribe the initials “S.D.G.” (Soli Deo Gloria) at the end of his compositions. This translates to:

“To God alone be the glory.”

This dedication, etched into his musical manuscripts, is a reflection of Bach’s profound religious faith. He saw his music as a conduit, a means of offering praise and glory to God. Would it then be justifiable, or even rational, to label such an indisputable prodigy as ‘primitive’ merely because his world view encompassed a belief in God?

Fast forward a few decades, and we meet another monumental figure in the realm of music, Ludwig van Beethoven. A name that, even to the least musically inclined, resonates with the echo of genius. Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata,” is far more than an arrangement of notes on a stave; it is a testament to the profound intellectual prowess, emotional depth, and technical mastery of its composer.

The endurance of the “Moonlight Sonata” as one of the most recognized and loved piano pieces underscores the sophistication of its era. Its timeless beauty reaches across the centuries, connecting us with a past that was as rich in emotional and intellectual depth as our present. Far from being ‘primitive’, our ancestors had a profound understanding of the world around them and within them, an understanding they articulated through the universal language of music. They were not just surviving; they were thriving, creating, and understanding their existence in a way that continues to resonate with us today.

In concluding this discourse, it becomes increasingly clear that the human understanding of the world, our interpretation of it, and our place within it has evolved and shifted throughout the epochs. Our modern viewpoint, while unique in its breadth and depth thanks to the technological and scientific advancements at our disposal, should not be regarded as inherently superior. This perspective stems not from a notion of ‘primitiveness’ among our ancestors, but from an evolution of knowledge built upon the foundations they laid down.

Dismissing the profound contributions of ancient civilizations simply because they didn’t share our contemporary scientific worldview is more than just narrow-minded-it’s a disservice to our collective intellectual heritage. It stunts our ability to fully grasp the spectrum of human history in all its rich and diverse glory. The ancient civilizations—the Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans, among others—were the architects of the world as we know it. Their impressive intellect, their boundless creativity, and their innovative spirit set the cornerstone for our modern world.

These civilizations navigated their existence, making sense of the world around them, creating intricate societies, and contributing to the sciences, arts, and humanities in ways that continue to inspire, inform, and influence us today. They showcased an advanced understanding of the world from their context, effectively employing their knowledge for practical applications and further developments.

The narrative that proposes our ancestors were savages, primitive in their outlook simply because their worldview differs from ours, is not only fundamentally flawed but also inhibits our potential for growth. It undermines the acknowledgement of our roots and the gratitude we owe to those who came before us, those who strived to comprehend their existence and the world around them, just as we do today.

Challenging and revising this narrative is, therefore, not just essential but imperative. By doing so, we pay homage to the brilliance of our ancestors, celebrating their genius instead of reducing them to misjudged caricatures of ignorance. We reaffirm the continuum of human curiosity, knowledge, and understanding, highlighting the collective journey we’ve embarked upon—the journey that has led us to this moment, here and now, where we stand on the shoulders of these giants of history.

In recognizing this, we weave together the tapestry of human intellect throughout the ages, appreciating the rich textures and patterns it presents. We validate the past, respect the present, and pave the way for a future where our descendants can look back at us, not as primitives, but as another crucial thread in the ever-evolving saga of human understanding and achievement.

Leave a comment